Journey into the Heart of the German Countryside – Part I

In the US we take great pride in our freedoms, often falsely thinking that they don’t exist in other lands. Or, not realizing that some freedoms may be greater in other countries. So it goes with freedom of mobility on foot. Try walking a 100 mile stretch in the US not located in some kind of state or federal park or preserve. It would mean walking the shoulder of a road, slave to the yellow line, in order to avoid trespassing. In Germany roads and tracks dissect field and forest and are all public access. This opens the geography to the hiker in such a way as to provide for dozens of potential routes to choose from between towns. Combine this with meticulously made German hiking maps and the possibilities for walking become endless.

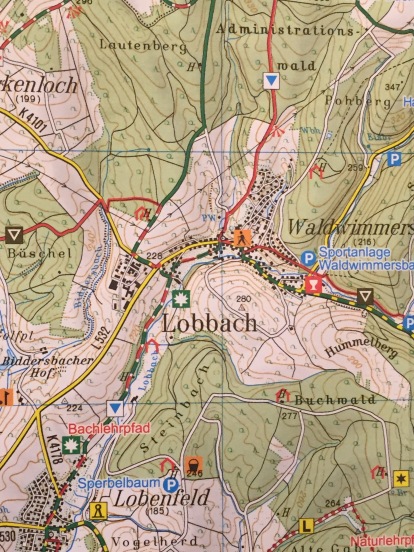

I had planned a 120 mile trek beginning in the town of Wiesloch on the western edge of the Kraichgau and ending at the medieval city of Rothenburg ob der Tauber. For weeks my dining room table was off-and-on covered with four hiking maps that spanned this stretch. With the aid of Google Earth I was able to plot a six day route with stays at taverns at the end of each day. At the end of my planning I discovered that my exact route was actually an ancient pilgrimage route – the Jakobsweg – between Rothenburg and the city of Speyer on the Rhine plain. The feet of ancient pilgrims had upstaged my clever cartographical analysis of the land.

This route is part of a vast web of pilgrimage trails that converge on the grave of the apostle Jacob in Santiago de Compostela in Spain. Since the Middle Ages the shell has been the symbol of the traveller on these trails and can been found showing the way on trees, walls, and fenceposts. The grooves on the shell represent the convergence of all trails in Spain.

My trek east was straightforward. The first third would take me across the rolling hill country of the Kraichgau. After crossing the Neckar River and climbing out of its deep valley I would traverse a small stretch of the relatively flat Bauland before dropping into the Jagst River Valley. After several days of meandering upstream alongside the Jagst I would emerge onto the Hohenlohe Plain for the final push to Rothenburg, situated above the Tauber Valley.

Day 1- April 28: Arrival

Driving away from the Frankfurt airport in a rental car after a transatlantic flight has its challenges. After negotiating the improbably narrow (at least by US standards) and twisting bowels of the rental car garage one is disgorged directly into fast-moving German traffic, necessitating instant decision making in order to get on the correct Autobahn. For much of the way south the Autobahn is entrenched in the sands of the Rhine Valley, hiding from view the castle-crowned hills of the Odenwald to the east. This is the same stretch of interstate where in 1938 race car driver Rudolph Caracciola broke the world speed record, reaching 432 km/hr in a Mercedes.

Those expecting to race at unlimited speed in this part Germany will be disappointed. Accelerate. Construction zone. Accelerate. “Stau” (bumper-to-bumper traffic). Stau. Stau. This is what happens when you have 81 million people living in a country smaller than the state of Montana.

Pure stands of pale-trunked Scotch Pine give way to corrugated farm fields of white asparagus. Unlike its green cousin, white asparagus develops completely underground in long, heaped rows of soil. The lack of sunlight prevents the growing stalks from photosynthesizing and turning green. The delicate stalks must be harvested by hand with a special knife just as they begin to emerge from the soil. This part of the Rhine valley is the epicenter of white asparagus cultivation. The vegetable is served as a side dish with butter, with hollandaise sauce, is sometimes fried, and often found on pizza.

I was ready for lunch. In the town of Wiesloch I stopped at my aunt and uncle’s house for a visit and lunch of white asparagus, ham, potatoes and hollandaise sauce. I risked a second glass of Mueller-Thurgau wine, hoping it would break my jet lag. Mueller-Thurgau is the second-most planted white grape in Germany after Riesling. A genetic cross between Riesling and Madeleine Royale grapes, it is perhaps the most misunderstood and under-appreciated wine on the planet.

Germans appreciate its ability to grow in substandard soil and its 4 – 6 Euro/bottle price tag. It was the consistent favorite of my students during long, parching hikes through the countryside.

Later in the afternoon I drove a few kilometers to the neighboring town of Nussloch, which straddles the slope of the eastern Rhine Valley. This is the town where my ancestors on my mother’s side lived for hundreds of years, where I attended grammar school off and on, and where I still posses a couple of small orchards. It is also the German town that lost its soul. With the exception of the small 18th century Lutheran church, there is very little that is old in the town. Nothing that speaks of the past or an identity. All the half-timbered houses are gone and only a very few old barns remain in town, with their red sandstone blocks filling in the spaces between the wooden framework. The last few decades have seen entire old neighborhoods replaced with modern buildings, shops and a retirement home. All towns in this region have a nickname for either the place or its residents. The inhabitants of Nussloch were referred to as the “moon sprayers”. As the story goes, one evening in 1911 the fire department rushed to the scene of a reported forest fire, only to find it was a fiery moon rising on the horizon. The delightful moon fountain, that for years stood at the town center, was replaced by a cold statue of an abstract figure standing in a pool next to what appears to be a pipe.

In Germany significant natural features such as landmark trees or small patches of forest of special ecological importance are often granted “Naturdenkmal” – natural monument – status. A few months before my arrival controversy surrounded the the town’s cutting down of its only Naturdenkmal tree, a large Linden planted in 1871 to mark the end of the Franco-Prussian war. Many towns have such “Peace Lindens.” It was the halfway point between my grandmother’s house and our family vineyard. My uncle often pulled us children in a wagon to the vineyard, with the familiar routine of “everybody gets out and walks at the Linden tree.” Standing beneath the tree in summer you could hear the faint droning of thousands of bees in the canopy overhead.

Much of the loss of the old buildings was beyond the immediate control of the town’s inhabitants. In early 1945, the town was subject to damaging allied air attacks. When American troops entered the town that spring, they showed their displeasure at one of the streets being named “Adolph Hitler Strasse” by commencing to destroy every other house along it. Only the protestant priest’s pleas stopped this plan from being completely carried out. All told, 59 houses were destroyed. It was on this street that I stayed the night at a tavern, spending the evening packing all the clothing, toiletries, first aid kit and rain gear I would need for the next six days.

Day 2 – April 29: Into the Kraichgau

Every good day in Germany begins with Broetchen, the breakfast rolls made in the early morning hours of each day by the local baker. They are made in an endless variety of size, shape, grain combination, and coating. No wonder that as children, we had to be quiet on our street as our neighborhood baker and his wife napped between 1 and 3 p.m. each day to catch up on their sleep.

After breakfast in the tavern I drove back to Wiesloch to park the rental car at my aunt’s house, shouldered my pack, said goodbye and headed east up the street that would lead me out of the Rhine Valley and into the rolling hill country of the Kraichgau. The area above Wiesloch is the easiest way to access the Kraichgau, since the Rhine Valley’s edge is less elevated here than to the north or the south. Soon I was off the asphalt, making my way through the fields and hedgerows along a farm track. The sky was a blue cap above. Behind me on the western horizon I could see the Vosges Forest rising dark behind the silhouette of the cathedral spires of Speyer on the Rhine Plain. To the north the Kaiserstuhl marked the beginning of the higher terrain north of the Kraichgau near the city of Heidelberg. Situated like a lighthouse on a hill to the south was the medieval fortress of the Steinsberg, often referred to as the “compass of the Kraichgau” since one can orient oneself from any point within view of it. The fortress is dominated by a tall stone tower, built atop the ancient remanent of a volcanic plug. It would be my companion for at least the first few days of my hike.

I had hit an exceptional bloom time. Apple and pear trees were in full blossom. Buttercups and rapeseed painted the fields yellow. The wheat – and the stinging nettles – were about knee high. Later in the season the nettles would tower over the wheat.

The Kraichgau is often referred to as Germany’s Tuscany because of its mild climate and mosaic of agricultural fields, orchards, vineyards, small towns and forests superimposed on a topography of rolling hills. To me it has always been a bit more mysterious, with its deep, shadowed sunken roads marking the path of medieval travelers – a bit more what I imagined the Shire of Tolkien’s works to be like. During my years as a child in Nussloch, my grandmother told tales of a dwarf named Gajemaenndl, who lived in a sunken road in the forest above town. Rarely glimpsed, he secretly helped wood cutters load wood if he deemed them good people, but played mischief with those of lesser moral integrity. My way now takes me through a sunken road towards the town of Zuzenhausen, where ancestors on my father’s side once lived and where an excellent brewery sits on the banks of the Elsenz, the Kraichgau’s largest stream. I’m only about halfway through my hike for the day but can’t resist a good glass of dark beer named Dachsenfranz (“Badger Franz”), named after a shadowy inhabitant of the local forests during the late 19th century until his disappearance during the first world war. He had fled his home country of Italy during the second independence war and made a home in the Kraichgau trapping badgers, martens and foxes. He sometimes worked for farmers and millers, ridding their buildings of mice and rats.

Later in the day I crest a hill and encounter a stone monument recounting the death of two young German aviators during world war 2, who died as their plane experienced “inadvertent contact with the ground.” Just outside of Waibstadt I pass by a large Jewish cemetery and mausoleum. The name of Weil is prominently inscribed across the front of the large structure. Hermann Weil established one of the world’s largest grain exchanges in Buenos Aires in 1889, later settled in Frankfurt before his death and burial here in 1927. His ashes, and those of his pre-deceased wife, were done away with during Kristallnacht in 1938.

Finally in Neckarbischofsheim I cross the tiny Krebsbach and make my way to the hotel. The first 17 miles of my journey felt good. No blisters or other ailments. Tomorrow I would have the company of two cousins for the day. Towns passed through: Wiesloch-Baiertal-Oberhof-Zuzenhausen-Daisbach-Waibstadt-Neckarbischofsheim. Streams crossed: Leimbach-Elsenz-Krebsbach. To be continued on next post…